Valerie Hsiung is a poet who writes between worlds, where language meets ritual and abolition meets afterlife. Her books dissolve the borders of poetry, prose, and philosophy into a single listening body, drawing on diasporic, ecological, and metaphysical inquiry. She is the author of eight full-length books, including The pedestrian (Nightboat Books, forthcoming), The Naif (Ugly Duckling Presse), The only name we can call it now is not its only name (Counterpath), featured in BOMB and The Poetry Project Newsletter, To love an artist (Essay Press), featured in Full Stop and Cleveland Review of Books, and outside voices, please (CSU). Her writing has appeared in Annulet, BathHouse Journal, The Georgia Review, mercury firs, The Nation, Paperbag, Verse and her work has been presented internationally at Double Change (Paris), Hyle (Athens), and the Jaipur Literature Festival. Recipient of support from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, PEN America, and Lighthouse Works, she teaches writing at the limits of language at the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University. Born to Chinese-Taiwanese immigrants in Cincinnati, Ohio, she now lives in the foothills of Colorado.

“Valerie Hsiung’s To love an artist is a work composed of dislocations--or rather, durations, expanses of dislocated voices, bodies, and narratives. It is a series of studies on ductility and leaching--what we are at our base and what we become when brought, whether violently or voluntarily, in proximity to others, other species of being, other modes of existing, other methods of naming: the lines we cross, “Language from bronze infects language from copper.” When the poet writes, “Today, I speak a language of brutes,” I read the enfoldment of the cruelty our collective and respective histories into the languages of our subjectivity. Any expression of self or free-ness or united-ness is laden with material and intentions that do not belong to us. We have been mixed forever, we have been poured and burned through borders always, and are ourselves burned and poured through. And that is why it is useful to invent forms for the expression of our alloyed selves, to be non-knowing. To love an artist presents a despondent, broken, scattered form. Yet, it pulses with nuance and engagement. It’s beautiful, irreverent, and dangerously incoherent. It stays with you when you’ve stopped reading it and puts your seeing in disarray. It nourishes and it fails and it teaches. This is a book of refusal. It is a cosmography written as metallurgy; it wants to be the dust and it wants to be the friction.”

- Renee Gladman

“To love an artist is to be drawn into her world so that you become a co-creator with her; To love an artist is to enter both a bestiary and topiary of language where the latter contorts and morphs through strange yet recognizable beauty; To love an artist is to enter the worlds of philosophy, history, politics, and most importantly the quotidian—passing seamlessly from poetry, to the essay, to reflection, to observation while remaining always within the landscape of poetry, as you navigate its repetitions and obsessions and become co-creator; it is to witness the play inherent in language as it meanders “the abyss between literacy and what (the poet) meant to say.” To love an artist is to indulge in a form of disquisitionary poetics with a sometimes wry humour and all the while looking at the world aslant. It is astonishingly original work—To love an artist.”

- M. NourbeSe Philip

- Renee Gladman

“To love an artist is to be drawn into her world so that you become a co-creator with her; To love an artist is to enter both a bestiary and topiary of language where the latter contorts and morphs through strange yet recognizable beauty; To love an artist is to enter the worlds of philosophy, history, politics, and most importantly the quotidian—passing seamlessly from poetry, to the essay, to reflection, to observation while remaining always within the landscape of poetry, as you navigate its repetitions and obsessions and become co-creator; it is to witness the play inherent in language as it meanders “the abyss between literacy and what (the poet) meant to say.” To love an artist is to indulge in a form of disquisitionary poetics with a sometimes wry humour and all the while looking at the world aslant. It is astonishingly original work—To love an artist.”

- M. NourbeSe Philip

“The only name we call it now is not its only name moves immediately beyond the realm of the bound book into an aeriel and psychedelic projection of mind, a continuously unfolding pattern that we can only ascertain from above the earth and through the concurrent music of clashing fragments. Hsiung’s text maintains its velocity and charm through perfectly timed peripheral detail giving way to the crystallized ongoing, luminous present. I never wanted to leave this book as it so closely illustrates the way a poet thinks back on reality: posing words as free-floating enclosures, sound being used as a necessary weapon of defense and our experience of being surrounded by language, helpless to continue listening and binding and throwing the line back out in new, unquantifiable formations.”

- Cedar Sigo

“Is it innocence to think that if you hold onto something long enough (community, relationship, attention) the habitual will give way to the extraordinary? The “person of insouciance” relating this logbook narrative evolves through the willful and unsuspecting ironies that threaten to foil the aim of artists and revolutionaries alike. The Naif so deranges intention with particulars—that is, with wonder—as to turn everyday fact into speculative fiction. A new way of living may yet prevail, thanks to Hsiung’s encouragement, akin to the spores of a mushroom, or to winning the lottery, waiting for us all along, as though in advance of the beginning.”

- Roberto Tejada

“A philosophical rumination that pulls us all the way into its depths, The Naif is an abstract painting made of words and sentences and punctuation or lack thereof, a distant memory whose skin you get to touch and feel as you attempt to find your way through its centers and peripheries. The Naif is an attempt for “reconciliation” between what we try to do in life while we have “already gone off course,” while we navigate an intimate piece of clothing dangling on a chair, cheese, mouse, juice gone bad, a lamp, a gift shop, all the what and the who of the everyday guiding us toward the word “transcend.” Kneading a slippery “new way of life” into a shape that is shifting and grounding, Valerie Hsiung shares with us her being in and out of community, in intimacy and in selfness. She invites us to “conduct ourselves according to the pulse of each other without losing the pulse of ourselves” while we immerse ourselves in the pulse of her beautiful language offering.“

- Poupeh Missaghi

“This book descends like a feral cloud from the abyss, able to change the weather of its reader through a hypnotic, swaying performance. A multidimensional braid of gestural vibrancy and "autobiographical transnational history" threads this temporally fluctuating lyric graveyard of intimate energies. Hsiung reminds readers to "slow down the vessel" to consider the ways in which the poet ionizes meaning, memory, and language itself, blurring the "frames within each frame" into new organisms rising and singing from the worm-rich mulch of The only name we can call it now is not its only name."

- Angel Dominguez

- Roberto Tejada

“A philosophical rumination that pulls us all the way into its depths, The Naif is an abstract painting made of words and sentences and punctuation or lack thereof, a distant memory whose skin you get to touch and feel as you attempt to find your way through its centers and peripheries. The Naif is an attempt for “reconciliation” between what we try to do in life while we have “already gone off course,” while we navigate an intimate piece of clothing dangling on a chair, cheese, mouse, juice gone bad, a lamp, a gift shop, all the what and the who of the everyday guiding us toward the word “transcend.” Kneading a slippery “new way of life” into a shape that is shifting and grounding, Valerie Hsiung shares with us her being in and out of community, in intimacy and in selfness. She invites us to “conduct ourselves according to the pulse of each other without losing the pulse of ourselves” while we immerse ourselves in the pulse of her beautiful language offering.“

- Poupeh Missaghi

“This book descends like a feral cloud from the abyss, able to change the weather of its reader through a hypnotic, swaying performance. A multidimensional braid of gestural vibrancy and "autobiographical transnational history" threads this temporally fluctuating lyric graveyard of intimate energies. Hsiung reminds readers to "slow down the vessel" to consider the ways in which the poet ionizes meaning, memory, and language itself, blurring the "frames within each frame" into new organisms rising and singing from the worm-rich mulch of The only name we can call it now is not its only name."

- Angel Dominguez

“Valerie Hsiung’s The only name we can call it now is not its only name takes us through the territory/lessness of the exiled: what is done to location, how one locates the self and community, and the journey to arrival should there be one. The tongue of the exiled contains multitude voices and forms. Hsiung’s poems speak to me about the performance of arriving at language reached through translations, through arrangements of letters that is also a displacement of other letters, territories, and bodies. The twists and detours in the story of “a place where I could not speak at first. I had to learn,” speaks also to the journey to language the autobiography of community. What we think of as voice is not free of the politics of dispossession. In this landscape, the only certainty is that of impermanence and of change. The poems resist the meanings we might ascribe to it, slip into forms when we think we know its name. It’s a stunning collection. “

- Tsering Wangmo Dhompa

- Tsering Wangmo Dhompa

“A storied, oscillating breath-scape, a wondrous tertium quid, Valerie Hsiung’s You & Me Forever maps a world that moves as simultaneously paradoxical, relational, and permutational. Edged with the epic, speech-based and strange, the writings enact the promise of dreams as they address matters of hauntings and bodies, displacement, and the nature of capital, exile, and art. Here the narrative ripples, achieves both temporal and spatial possibilities, works both boundariness and dissolve. A destabilizing marvel.“

- Hoa Nguyen

"The first time I read Valerie Hsiung’s You & Me Forever, I had a vision of a bonfire in which countless volumes of love-twisted and love-twisting works of literature, including sculptures and films, were reduced to ash, and from the ashes were intuitively yet precisely drawn filaments on which were inscribed prophetic dialogues that voiced the poet’s relationship with the forces that would come to make, and perpetually threaten to unmake, her world. The second time I read You & Me Forever, there was neither filament nor fire, but an animated frieze, or maybe rainfall, or serrated light, of intimate retribution, that is retributive intimacy. I say read, but that is not exactly what happened."

- Brandon Shimoda

“In the fleeting, quicksilver language of Valerie Hsiung’s You & Me Forever, accumulated peripheries jostle, rock on the waters, gain some traction, but they never quite settle. The worlds Hsiung delicately folds together create friction, a low steady hum builds and then disperses — only to try and build again. We, the reader, are invited to sit inside the hum of this continual construction, to place our bodies in the chamber alongside the many other bodies that fill You & Me Forever. A thread pulls us along. What saline logic this book holds.”

- Asiya Wadud

- Rosa Alcalá

"In this shifting assemblage of verse, prose poems, scenes, performance scores, charts and maps, ‘Time unjumping from windows,’ Hsiung’s speaker emerges through clashes of language and its structures—its traumatized syntax, its colonialist dictionaries, its abusive evasions, its obfuscating corporate speak, its xenophobia and its patriarchalism, and its capacity to scorch and dazzle. Out of the urgent ‘confrontation of language,’ outside voices please issues an utterly new invitation into and beyond language: ‘Let us form the obtuse and acute angles of this assaulted triangulation.’"

- Lauren Russell

"Valerie Hsiung’s outside voices please is earful of delicate worms wriggling and crisscrossing ocean box. Scattered mouths on its own island. Ocean twisting full of video monitor eyes paging through dead news. Girl flipped around bench tasting each hinge in plastic word. What’s in pocket of each word, the books asks of blurred language? Savage corner you turn around, angle your eye slides down, a close record of each infiltration."

- Ching-In Chen

"In this shifting assemblage of verse, prose poems, scenes, performance scores, charts and maps, ‘Time unjumping from windows,’ Hsiung’s speaker emerges through clashes of language and its structures—its traumatized syntax, its colonialist dictionaries, its abusive evasions, its obfuscating corporate speak, its xenophobia and its patriarchalism, and its capacity to scorch and dazzle. Out of the urgent ‘confrontation of language,’ outside voices please issues an utterly new invitation into and beyond language: ‘Let us form the obtuse and acute angles of this assaulted triangulation.’"

- Lauren Russell

"Valerie Hsiung’s outside voices please is earful of delicate worms wriggling and crisscrossing ocean box. Scattered mouths on its own island. Ocean twisting full of video monitor eyes paging through dead news. Girl flipped around bench tasting each hinge in plastic word. What’s in pocket of each word, the books asks of blurred language? Savage corner you turn around, angle your eye slides down, a close record of each infiltration."

- Ching-In Chen

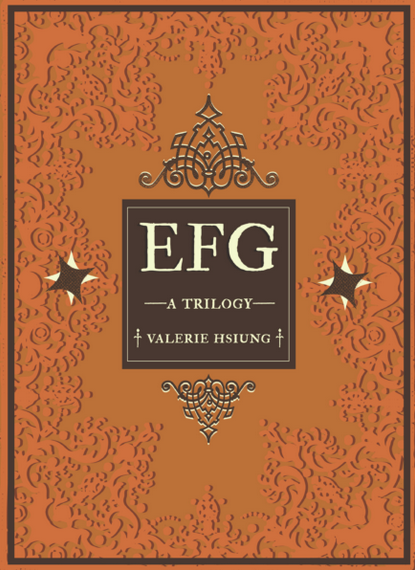

- e f g (Action Books, 2016)

-

YOU & ME FOREVER (Action Books, 2020)

-

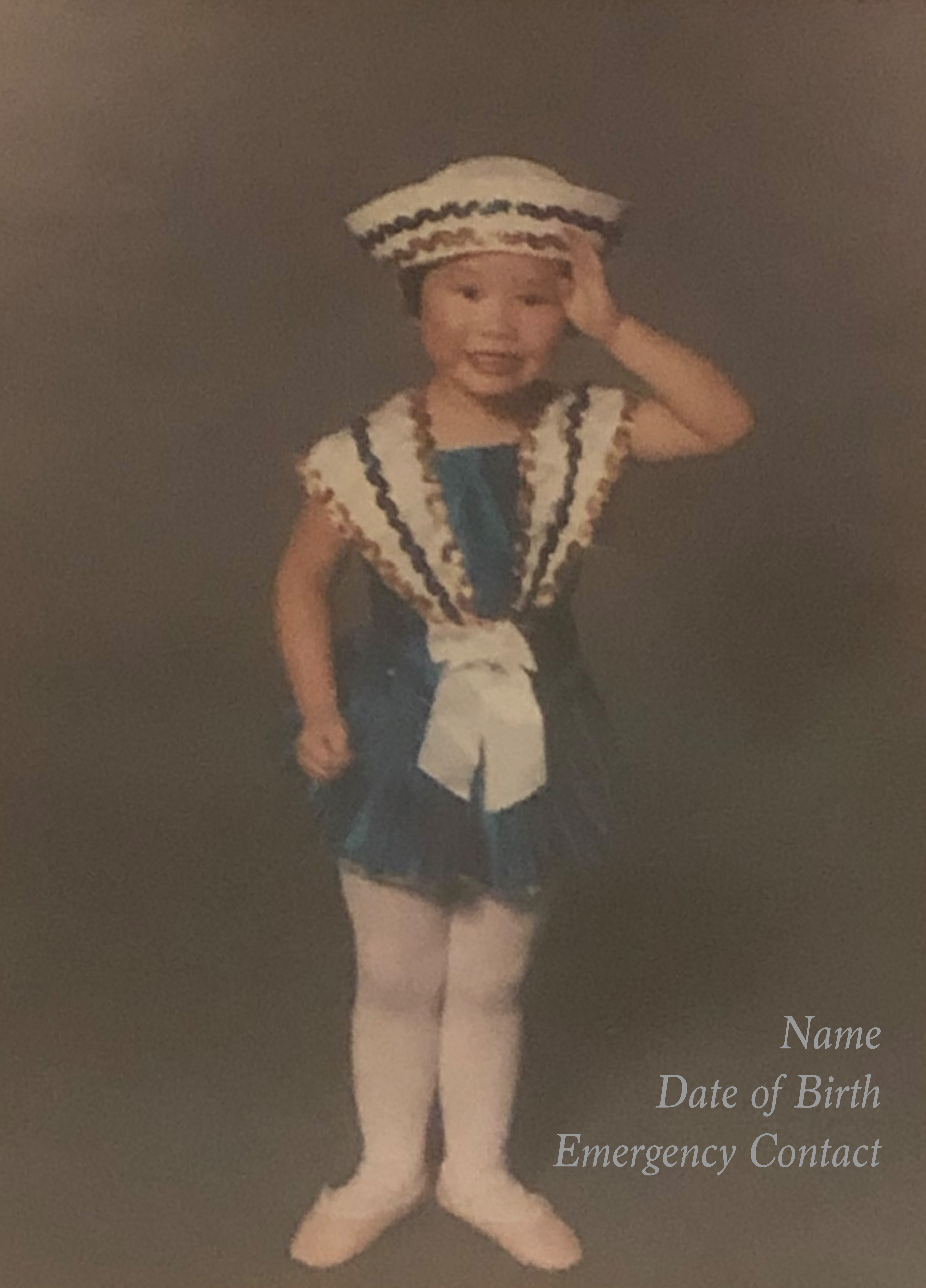

Name Date of Birth Emergency Contact (The Gleaners, 2020)

- outside voices, please (CSU, 2021)

- To love an artist (Essay Press, 2022)

- The only name we can call it now is not its only name (Counterpath, 2023)

- The Naif (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2024)

- The pedestrian (Nightboat Books, 2026)

from Pearls in Paperbag, 2024

from Hostending in Paperbag, 2024

from Untitled in new_sinews, 2024

from The Naif in The Georgia Review, 2024

from Untitled in mercury firs, 2024

from A superstitious poem in The Nation, 2024

from The only name we can call it now is not its only name in digital vestiges, 2023

from Untitled in Etcetera, 2023

from The only name we can call it now is not its only name in BathHouse Journal, 2022

from The only name we can call it now is not its only name in Annulet, 2022

from To love an artist in Verse, 2022

from To love an artist in Chicago Review, 2022

from Tell Me How It Makes You Feel in The Believer, 2020

Review in The Poetry Project Newsletter by imogen xtian smith, 2023

Interview in BOMB Magazine with Angie Sijun Lou, 2023

Review in Cleveland Review of Books by Megan Jeanne Gette, 2023

Review in Full Stop Magazine by Isabel Sobral Campos, 2023

Interview in Matter Monthly with Tiffany Troy, 2023

Review in Tupelo Quarterly by Amanda Auerbach, 2022

Interview in Tupelo Quarterly with Mary-Kim Arnold, 2022

Interview in Exclamation’s Gaunlet with Clarissa Jones, 2022

Review in Angel City Review by Anahita Safarzadeh, 2020

Interview in Tarpaulin Sky Magazine with Julia Cohen, 2020

April 18th 2026 Saturday 2:30pm ET

Voices in Disguise, New Orleans Poetry Festival at New Orleans Healing Center (New Orleans, LA)

w/ Stella Corso, Bo Hwang, Zack Darsee, Elise Houcek

March 7th 2026 Saturday 2:00pm ET

Reading of the Fire Horse at The Compound (Baltimore, MD)

w/ Christine Shan Shan Hou, Stine An, Emily Lee Luan, Jimin Seo, and Ruby Mars

March 6th 2026 Friday 4:00pm ET

Essay Press at Meander Art Bar (Baltimore, MD)

w/ Jill Magi, Steffan Triplett, Kate Colby, Mary-Kim Arnold, Silvina Lopez Medin, Julie Carr, Rodrigo Toscano

March 6th 2026 Friday 3:00pm ET

Author Signing at Nightboat Booth AWP Bookfair, Baltimore Convention Center (Baltimore, MD)

March 5th 2026 Thursday 8:00pm ET

Nightboat Books at Red Emma’s Bookstore (Baltimore, MD)

w/ Aditi Machado, Aurora Mattia, Brian Teare, Chia-Lun Chang, Cyree Jarelle Johnson, Kimberly Alidio, Mónica de la Torre, Miranda Mellis, Soham Patel, Tisa Bryant

July 21st 2024 Sunday 4:00pm ET

Belladonna’s GIST at Vale of Cashmere, Prospect Park (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Gia Gonzales

July 18th 2024 Thursday 7:00pm ET

Honey’s (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Ben Claus, Brian Alarcon

July 11th 2024 Thursday 6:30pm ET

Twenty Stories (Providence, RI)

w/ Eleni Sikelianos, Darcie Dennigan, Tess Brown-Lavoie

June 27th 2024 Thursday 7:00pm CET

Double Change at Atelier Michael Woolworth (Paris, FR)

w/ Etaïnn Zwer, Johanna Skibsrud

June 20th 2024 Thursday 7:00pm MT

Jack Kerouac School SWP 50th Anniversary Faculty Reading (Boulder, CO)

w/ Dawn Lundy Martin, Stella Corso, Monica Jiménez

May 30th 2024 Thursday 8:30pm ET

Domestic Water at Conveyor Belt Books (Cincinnati, OH)

w/ Cathy Wagner, Harris Wheeler

May 11th 2024 Saturday 7:00pm ET

Ugly Duckling Presse Spring Studio Party at The Old American Can Factory (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Alex Cuff, Fatemeh Shams, Kendra Sullivan

May 8th 2024 Wednesday 7:00pm MT

Fatelessness On the Mend Fatelessness On the Lam at Counterpath (Denver, CO)

w/ Bo Hwang, Ben Claus, Shreeya Shrestha

Mar 13th 2024 Wednesday 6:30pm MT

Visiting Poet at University of Colorado (Boulder, CO)

Nov 2nd 2023 Thursday 7:00pm ET

Bar Redux (New Orleans, LA)

w/ Gabrielle Octavia Rucker, Henry Goldkamp

Oct 28th 2023 Saturday 6:00pm ET

Visiting Poet at Lighthouse Works (Fishers Island, NY)

Oct 19th 2023 Thursday 6:30pm MT

And Now: Featuring at Trident Books (Boulder, CO)

w/ Jade Lascelles, Mike Young, Gion Davis

Oct 6th 2023 Friday 7:00pm MT

FRAME Reading Series at East Window Gallery (Boulder, CO)

w/ Andrea Rexilius, Eric Baus, Molly Leclair

Sept 28th 2023 Thursday 7:00pm ET

Essay Press Reading (Virtual)

w/ Dennis James Sweeney, Orchid Tierney

Aug 3rd 2023 Thursday 6:30pm ET

Exquisites Reading Series at Art Cafe & Bar (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Andrea Abi-Karam, Maura Modeya, Em Marie Kohl, Danilo Machado

Jul 16th 2023 Sunday 4:00pm ET

NOMAD Reading Series at Grandchamps (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Wo Chan

June 29th 2023 Thursday 7:00pm MT

Jack Kerouac School SWP Faculty Reading @ Naropa (Boulder, CO)

w/ Layli Long Soldier, Tongo Eisen-Martin, Amy Bobeda

May 27th 2023 Saturday 7:00pm ET

Salon Salvage at Weathered Wood Studio (Troy, NY)

w/ Brandon Downing, Cynthia Hogue, Olivia Muenz

May 15th 2023 Monday 8:00pm ET

The Poetry Project (New York, NY)

w/ Ada Smailbegovic

Apr 13th 2023 Thursday 7:00pm ET

Book Launch for Carrie Oeding’s If I Could Give You a Line @ Twenty Stories (Providence, RI)

w/ Mary-Kim Arnold, Carrie Oeding

Mar 10th 2023 Friday 8:00pm PT

AWP Off-Site: Futurepoem, Action Books, Switchback @ Bad Bar (Seattle, WA)

w/ Ghayath Almadoun, Julie Carr, Jessica Q. Stark, Paul Cunningham, & more

Mar 10th 2023 Friday 7:00pm PT

AWP Off-Site: Essay Press & Kelsey Street @ Common Area Maintenance (Seattle, WA)

w/ Diana Khoi Nguyen, Andrea Abi-Karam, Steven Dunn, Dennis James Sweeney & more

Mar 10th 2023 Friday 6:00pm PT

AWP Off-Site: Counterpath @ Ada’s Technical Books & Cafe (Seattle, WA)

w/ Ronaldo V. Wilson, Edwin Torres, Rae Armantrout, Eleni Sikelianos, Rodrigo Toscano, Urayoan Noel & more

Mar 9th 2023 Thursday 7:00pm PT

AWP Off-Site: CSU, Rescue, Annulet @ Bad Bar (Seattle, WA)

w/ Sara Deniz Akant, Rajiv Mohabir, Mike Walsh, Adrienne Raphel, Sarah Minor, & more

Nov 2nd 2022 Wednesday 7:00pm ET

Poet-in-Residence Reading @ University of Notre Dame (South Bend, IN)

w/ Mike Corrao

Oct 27th 2022 Thursday 7:00pm ET

Greetings Reading Series @ Unnameable Books (Brooklyn, NY)

w/ Dara Barrois/Dixon, Brittany Dennison

Oct 17th 2022 Monday 7:00pm MT

Jack Kerouac School Fall Symposium Faculty Reading @ Naropa (Boulder, CO)

w/ Steven Dunn, Michelle Naka Pierce

Oct 13th 2022 Thursday 8:00pm ET

BathHouse Journal Volume 23 Launch Celebration (Virtual)

w/ Jocelyn Saidenberg, Deborah Meadows, Dinisha Thompson, Megan Duffy, Mack Gregg

Oct 1st 2022 Saturday 1:00–2:30pm PT

Ten Years of Convergence @ University of Washington, Bothell (Virtual)

w/ Cecilia Vicuña, Tracie Morris, Andrea Abi-Karam, Kazim Ali, Yanara Friedland, Jen Hofer, Philip Metres

Sept 23rd 2022 Friday 7:00pm MT

Counterpath (Denver, CO)

w/ Eric Baus, Ahja Fox, Peter Gizzi